What's behind Ikigai, Ho'oponopono, Meraki, Lykke - and our search for happiness

The search for happiness is not a destination, but a centuries-long journey that connects cultures and times. Terms such as Ikigai from Japan, Ho'oponopono from Hawaii, Meraki from Greece or Lykke from Denmark invite us to look at life from new perspectives. They sound promising and inspire us to reflect on a fulfilled life. What new perspectives can we gain from them on the question of what constitutes a fulfilled life?

Ikigai: Origin and Misunderstanding

Ikigai is deeply rooted in Japanese culture and means 'what makes life worth living'. Made up of the syllables 'iki' (life) and 'gai' (value), it describes both the big goals in life and the appreciation of the small moments in everyday life. In Japan, it is an everyday concept that is not limited to spectacular achievements, but is expressed in simple things - a walk, a meal or a conversation.

Mieko Kamiya and Ikigai

Doctor, psychotherapist and researcher Mieko Kamiya wrote about the importance of ikigai in her 1966 book Ikigai-ni-Tsuite, comparing it to Viktor Frankl's concept of the search for meaning. Kamiya, who lived in the USA and Geneva and accompanied leprosy patients in Japan, emphasised that ikigai is not only rooted in the achievement of goals, but above all in the experience of everyday life. Her book was a huge success in Japan, and Japanese television dedicated an entire series to her - but her work has not yet been translated into other languages.

In the West, however, ikigai is often associated with a Venn diagram. This model was developed in 2012 by Spanish astrologer Andrés Zuzunaga under the title 'Propósito'. It combines the four areas of passion, talent, social needs and income. At a time when traditional sources of meaning, such as religion and family, are becoming less important, it struck a chord and was linked to Ikigai by blogger Marc Winn. In 2014, Winn published the diagram as 'Ikigai' and combined it with reports of 'Blue Zones' where people live particularly long and contented lives.

This link has little to do with the original Ikigai. While the Venn diagram offers a concrete formula for meaning, in Japan ikigai is understood as an individual and changing way of life. This misunderstanding illustrates how easy it is in the West to look for simplistic solutions without taking into account the cultural context.

Hedonism vs. eudaimonia: the sustainable path to happiness

Ikigai emphasizes the inner sources of happiness and focuses on everyday pleasures through the central question: What, no matter how small, makes my life worth living? Rather than the Western approach of asking, "What can I do to become happy?" Ikigai invites reflection: "How do I want to shape my life, and what treasures already present in my life remind me that happiness is possible now?" This perspective aligns with the concept of eudaimonia, which has gained increasing attention in positive psychology and happiness research.

In psychology, happiness is often categorized into two forms: hedonism, which centers on short-term pleasure, and eudaimonia, which is rooted in meaning, personal growth, and alignment with one’s core values. Studies by Ryan and Deci (2001) and Seligman (2002) show that while hedonistic happiness may offer immediate gratification, it is often fleeting. Eudaimonic happiness, on the other hand, fosters lasting satisfaction as it is built on deeper values and a conscious engagement with life.

Ikigai embodies the eudaimonic approach uniquely by shifting focus away from fleeting pleasures or specific achievements toward the fulfillment found in the act itself. A compelling example is the Japanese tea ceremony, where each step is performed with mindfulness, emphasizing the process rather than the outcome. The tea is not simply a goal; it is a moment of presence and intention.

This practice illustrates a profound truth: the moment is fleeting, yet it holds immense significance. By paying attention to these seemingly small instances, we create lasting values for our happiness. Positive psychology terms this values-based happiness – finding joy in alignment with what deeply matters. Hedonic pursuits, such as material acquisitions, may enhance comfort and pleasure, but they rarely foster enduring fulfillment. Ikigai offers a lens through which we can recognize and honor the richness of such moments.

© Motoki, Japan, 2016

Ikigai and the conscious use of money

Ikigai invites us to find meaning and fulfilment in the big and small things in life. Although money is not a central part of Ikigai, our use of money can be a reflection of what we value and how we create meaning in our everyday lives. In Western culture, money plays an important role: it is associated with a good life as it enables access to health, culture, education and social participation. But the question remains: Does money really make us happy?

This is where research by Dunn, Aknin and Gilbert offers interesting insights. Their study ‘If Money Doesn't Make You Happy, Then You Probably Aren't Spending It Right’ sheds light on how we can increase our well-being through the way we use money. It shows that it is less about how much money we have and more about how consciously we use it.

01 Experiences take precedence over things

Material purchases often only provide short-term pleasure, while experiences such as travelling, concerts or spending time with friends create more lasting memories. These experiences not only enrich our lives, but also strengthen social connections - an important aspect of Ikigai. At its core, Ikigai reminds us that the joy of the experience itself is more valuable than the things we own.

02 Giving makes you happier than receiving

The study shows that prosocial spending - spending money on others - increases our own happiness more than selfish consumption. A small gift, a donation or the support of a friend creates a connection and a sense of purpose that fulfils us. Ikigai emphasises the importance of such moments of resonance. They make us realise that our lives gain value through the positive impact we have on others.

03 Small pleasures instead of big purchases

Regular, small pleasures have a greater effect on our well-being than infrequent large purchases. A spontaneous meal with friends, a visit to nature or a good book bring recurring joy into everyday life. These small pleasures are in line with the principles of Ikigai, which teach us to appreciate the moment and see the value in the everyday.

04 Anticipation and conscious planning promote happiness

Another key to happiness lies in anticipation. When we consciously work towards something or look forward to an experience, the positive feeling is prolonged. Ikigai encourages us to savour these small moments of anticipation and see them as part of the experience. Conscious planning and mindful handling of money can thus be a tool to make life more fulfilling.

Integrating Ikigai into life: From Five to Six Pillars

Ken Mogi originally described Ikigai as a concept with five pillars: Being in the moment, joy in small things, self-acceptance, harmony and sustainability. Ken Mogi had already finished his book on Ikigai when he thought about how he could finalise it during one of his daily walks through Tokyo. These walks, which gave him time to think and reflect, eventually led him to the idea of condensing the essence of Ikigai into five pillars. These five pillars - being in the moment, joy in small things, self-acceptance, harmony and sustainability - found their place on the final pages of his book and formed the conclusion of his work.

However, on closer inspection, it became clear that two of the pillars, harmony and sustainability, are independent dimensions. Harmony, as a value deeply rooted in Japanese culture, can already be found in Japan's first constitution and is still very important today. The current era in Japan bears the name ‘Reiwa’, which means ‘beautiful harmony’, a designation proclaimed by former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who passed away in 2022. Sustainability, on the other hand, is a response to the challenges of the modern world and complements the values of harmony by emphasising mindfulness towards the environment and future generations.

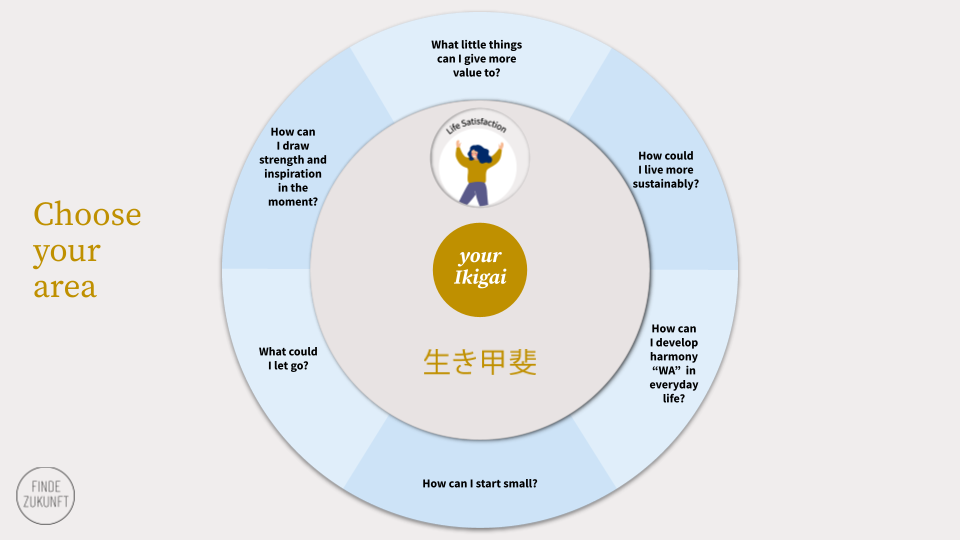

In a conversation with Ken Mogi, we jointly developed the idea of turning these five original pillars into six dimensions. When we asked how these six dimensions relate to each other, Ken Mogi said: ‘They are all connected anyway.’ This connection makes it clear that Ikigai is not just a collection of principles, but a holistic model for conscious living.

The six pillars of Ikigai offer orientation and can enrich everyday life:

Being in the here and now: Promoting mindfulness and presence.

Enjoy the little things: Recognising the value in the everyday.

Self-acceptance: Accepting yourself and others.

Harmony: Living in harmony with others.

Sustainability: Shaping change mindfully.

Freedom: Preserving the space for personal fulfilment.

This extension of the model combines traditional values with the challenges of the present. It serves as the basis for our own model at Finde Zukunft, which provides practical support for both meaning and well-being. It is a tool to shape one's own lifestyle more consciously and to find fulfilment in the small and big moments of life.

Ikigai is a bow to our own lives

Japanese culture is deeply rooted in respect, a value that permeates many aspects of daily life. This is vividly demonstrated at football matches, where Japanese fans not only leave their own areas spotless but also clean up the rubbish left by ‘opposing’ fans. This collective sense of responsibility and care extends far beyond stadiums.

Public spaces in Japan are treated with the same respect. It is common to see people ensuring that parks, sidewalks, and shared spaces are left cleaner than they found them. Public toilets, which are often spotless despite high usage, are a reflection of this cultural mindset. Respect for shared spaces is not seen as an obligation but as a natural extension of gratitude for the community.

This respect is also evident in the everyday acts of kindness extended to strangers. For instance, if someone struggles with directions, it is not unusual for a passerby to walk them to their destination, even if it means going out of their way. During natural disasters, such as earthquakes, this culture of mutual support becomes even more apparent, with communities coming together to help one another rebuild and recover.

Respect is perhaps most visible in the way people greet each other in Japan, almost always with a bow. This centuries-old custom comes in many forms, with the depth and duration of the bow reflecting the level of respect being shown.

When you think about the act of bowing, it is, in essence, an intentional pause. It is a moment to acknowledge, reflect, and honour the presence of another. This symbolism extends to a broader philosophy:

‘Our western life is characterised by doing. We find confirmation in our activities and in finding solutions. We are in search of the next project. A regular (active) break is a wonderful interruption that can help you to recognise your Ikigai. It makes you realise what makes your life worth living. The pause is a bow to your own life.’

Ikigai encourages us to pause—not to stop, but to be present. It invites us to honour the small, fleeting moments that reveal life’s meaning and value. The secret of happiness lies not in monumental achievements, but in embracing and experiencing the everyday with intention and gratitude.

Experience Ikigai in everyday life - Some Exercises for you

Ikigai is not an abstract philosophy, but a concept that can be experienced in daily life. With these simple exercises, you can strengthen your own connection to the principles of Ikigai and consciously create moments that enrich your life:

01 Gratitude: Recognise your own contribution

Start or end your day with a short reflection. Write down three things you are grateful for. They can be small or big things - the warm tea you had in the morning, a smile you received or a project that was a success. The crucial step is to consider what contribution you have made to these moments. Did you prepare the tea with special care? Through this reflection, you realise how much influence you have on the beautiful moments in your life. This awareness strengthens your sense of purpose and promotes value.

02 Reflection on values: Exploring the resonance space

Take time to think about what is really important to you. Values are the silent guard rails of our lives and show us what fulfils us deep inside. A good way to start this reflection is to go for a walk. As you walk, observe your surroundings. Perhaps your gaze will linger on something - a tree, a child playing, a work of art in a shop window. Perhaps you strike up a brief conversation with a neighbour or hear a song that triggers something in you.

Use these moments of resonance to listen to yourself and realise what is valuable to you. You can then record these impressions in writing. Describe not only what you experienced, but also why this moment was special for you. What touched you about it? And what was your own part in it? Was it your conscious perception, your openness or your interest?

These little ‘ikigai moments’ can help you to discover sources of meaning and joy in your life. Over time, you will recognise a pattern - values and activities that repeatedly have meaning for you. These insights are a guide to your personal Ikigai.

03 bring joy: Enrich others, give yourself a gift

A simple but transformative exercise is to look for small ways to bring joy to others. This can be a friendly ‘good morning’, a small gesture of help, a handwritten note or simply listening attentively. When we make others happy, we often experience a deep sense of satisfaction. Studies show that prosocial acts - i.e. things that benefit others - can increase our own happiness.

The power of this exercise lies in the fact that it connects us with others. When we consciously realise how our small actions make a difference, it creates a sense of resonance and purpose. Here too, it's worth keeping a record of the moments: What did you do, how was it received, and how did you feel about it yourself? This reflection deepens our understanding of how much we also enrich ourselves through giving.