Mieko Kamiya – the Founder of Ikigai Psychology

„There is nothing more for humans to live life fully than IKIGAI. Therefore there is no cruelty greater than to deprive humans of their ikigai, and there is no greater love than to give humans their ikigai.“

Illuminating Ikigai: The Enduring Wisdom of Mieko Kamiya

Mieko Kamiya is the true founder of Ikigai Psychology. We want to honour her contributions with our books, courses and articles. She is not famous, even in Japan, but at least there is a dedicated series on Japan's first television channel, NHK, including an animated film that brings her life story to life. Despite her acclaim in Japan, Kamiya's groundbreaking work has remained relatively obscure beyond its borders, a surprising oversight given her pivotal role in the foundational research and development of Ikigai psychology.

The Western Ikigai Misconception

Ikigai, a concept that has captured the global imagination for its promise of finding deep personal fulfillment and purpose, is often mistakenly simplified to a popular Venn diagram by Andrés Zuzunaga, leading many to equate Ikigai with a mere intersection of personal and professional satisfaction. However, Kamiya's exploration of Ikigai reveals a tapestry far richer and more intricate than such reductive interpretations suggest.

The Limitations of the Western Ikigai Diagram

The problem with simplifying Ikigai to the popular Venn diagram by Andrés Zuzunaga (originally coined as “Propósito”)* lies in its reductionist approach, which could potentially mislead individuals into equating the profound and multifaceted concept of Ikigai with just the intersection of personal and professional satisfaction. This oversimplification overlooks the richer and more intricate essence of Ikigai as explored by Mieko Kamiya and others, who emphasize its depth and complexity, akin to the spectrum of life itself.

The Four Purpose Questions that are not related to the true meaning of Ikigai

The Venn diagram poses four key questions:

What do I love?

What am I good at?

What can I do to make money? and

What does the world need?

While these questions might be useful for career planning or job searching, they fall short in encapsulating the true spirit of Ikigai.

By including "What can I do to make money?" as one of its central queries, the diagram inherently links the meaning of life with financial success, which can be misleading and potentially harmful. This association might lead individuals to prioritize monetary gain over genuine fulfillment, passion, and contribution to society, diverting them from the true exploration of Ikigai, which is meant to be a personal and internal journey rather than an external pursuit of wealth or status.

Job Search Aid, Life Meaning Hazard: The Purpose Diagram Dilemma

In essence, the problem with the Venn diagram's simplistic representation is that it dilutes Ikigai's comprehensive nature, reducing it to a formulaic intersection of elements that can be easily resolved. This not only misrepresents the cultural and philosophical depth of Ikigai but also risks leading individuals away from a more meaningful, introspective, and personal exploration of their life's purpose. True Ikigai is about finding joy, fulfillment, and balance in every aspect of life, beyond the confines of career and financial success, encompassing a deeper connection with one's values, community, and the simple pleasures of life.

Your career doesn't visit you in hospital.

If you can no longer perform, it will let you down. Money and success are nice and hedonistic pleasures, but it's dangerous to hang your life on them. I know this from my own life experience.

The true Ikigai is about: What makes life worth living? This can lead us to simple yet beautiful moments. We can find joy and meaning in the simplest things in our daily lives.

– Motoki Tonn, Author on Ikigai, Penguin Random Hourse

Ken Mogi, another esteemed scholar in the field, describes Ikigai as a "spectrum," emphasizing its complexity and depth, mirroring the multifaceted nature of life itself.

„Ikigai can be something small or something big. Ikigai is a spectrum. And the complexity of ikigai actually reflects the complexity of life itself.

“

Ikigai as a Dynamic Quest: Kamiya's Vision of Meaningful Living

Mieko Kamiya's work serves as a crucial cornerstone in understanding Ikigai, not as a simplistic formula for happiness but as a nuanced and dynamic pursuit of meaning that resonates with the individual's innermost values, passions, and capabilities. Her legacy in Ikigai research offers invaluable insights into the pursuit of a life imbued with significance, joy, and a profound connection to one's inner self and the world around.

Mieko Kamiya’s life and professional work

Mieko Kamiya's deep involvement with leprosy patients, who faced extreme social exclusion, uprooting from their families, and imprisonment due to their condition, laid a crucial foundation for her work in Ikigai psychology. Her interactions with these individuals, who, despite enduring profound suffering and isolation, continued to find reasons to face each day, propelled Kamiya to explore the essence of what makes life worth living. Ikigai is a nuanced and dynamic pursuit of meaning, deeply resonant with an individual's innermost values, passions, and capabilities.

Kamiya's significant contributions to both the medical and psychological fields are immortalized in Hansen's Disease (leprosy) memorial centers named in her honor. Kamiya's centers not only pay tribute to her unwavering commitment to marginalized individuals but also serve as a guiding light for those seeking a profound understanding of Ikigai, surpassing the superficial interpretations commonly found in mainstream media.

Education

Doctor of Medicine, Osaka University (1960)

Her academic dissertation was “Rai no seishin igakuteki kenkyu (Psychiatric research on Hansen’s disease)”

Graduated Tokyo Jyoshi Igaku Senmongakko (1944; Tokyo Women’s Medical Vocational School)

Graduated Regular class of Tsuda English cram school (1935)

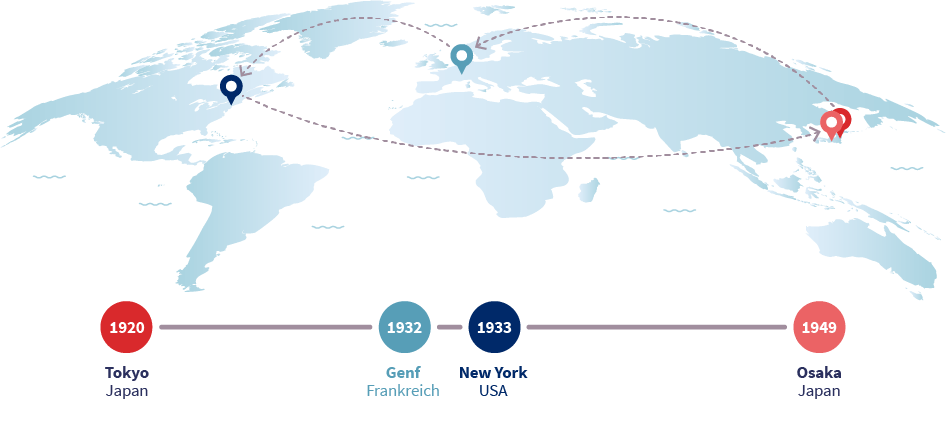

Landmarks

1923 Lived in Geneva, Switzerland

1938 Entered Department of Science (Premed), Columbia University, the U.S.

1941 Transferred to Tokyo Jyoshi Igaku Senmongakko (Tokyo Women’s medical Vocational School)

1944-1949 Entered Psychiatry office of Tokyo Imperial University

1952-1960 Researcher of Clinical psychiatry in the Department of medicine, Osaka University

1954 Associate professor of Kobe College

1957-1972 Adjunct staff at National Sanatorium Nagashima aiseien

1959 Associate professor at Kobe College

1960-1964 Professor at Department of Sociology, Kobe College

1963-1976 Professor at Tsuda College

1965-1967 Medical director of Clinical psychiatry, Osaka University

Adjunct staff at Tsuda College

Contributions

She contributed to clinical psychology in Japan, and also helped patients who suffered from Hanses’s disease in National Sanatorium Nagashima aiseien. She also suggested breath of life and improved understanding of Hansen disease by publishing books.

„There is nothing else for human beings to live life fully than Ikigai. Therefore, there is no greater “cruelty” than depriving people of their ikigai, and there is no greater love than giving people their ikigai.“

Mieko Kamiya did not only do research on ikigai. She was a doctor, psychiatrist and author - she started writing at the age of nine in her diary (called “shuki”).

Mieko Kamiya – A Linguistic Expert

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, translated by Mieko Kamiya

Mieko Kamiya worked as a translator for the imperial court, which included serving as a private tutor for Princess Mishiko. Her ability to speak and teach several foreign languages, including French, German and English, showcases her exceptional linguistic talents. Among her notable translations is the work of Marcus Aurelius into Japanese, bringing the Meditations of this Stoic philosopher to a Japanese audience.

Her academic and literary contributions were further enriched by her translations of works by Michel Foucault, a profound influence in the fields of philosophy, sociology, and critical theory. Her ability to convey the complex ideas of Foucault, as well as those of other Western philosophers and authors, into Japanese, highlights her role as a bridge between Eastern and Western thought.

Her engagement with Foucault's work, known for its critical examination of societal institutions and power structures, including psychiatry, complements her deep involvement with marginalized communities, such as leprosy patients. Kamiya's work with these patients, who faced extreme social exclusion and uprooting from their families, informed her nuanced understanding of Ikigai. She sought to understand how individuals find meaning and purpose despite being deprived of their basic human dignity and rights.

Mieko Kamiya as a Teacher

Mieko Kamiya's profound insights into Ikigai were not only derived from her professional roles as doctor, psychiatrist and writer, but were deeply personal, shaped by a life of self-doubt, loss and tragedy. Despite the widespread belief among her peers that her work with lepers was her ikigai, Kamiya's own reflections reveal a different source of fulfilment. Her diary entries provide a window into her soul, illustrating how her true ikigai emerged from her research and writing on the subject itself.

„At the exhibition and on the train ride home, I continued to ruminate on it, repeating before me the phrase: ‘Devote the rest of your life entirely to this task!’ I should finish my dissertation as soon as possible so that I could begin the work of fulfilling my mission.“

Kamiya's diary entries, such as "I must write" and reflections on dedicating her life to understanding ikigai, underline the central role of writing in her life. Despite the social value placed on her medical and philanthropic work, it was in the quiet moments of reflection and writing that Kamiya found her deepest sense of purpose. Her diary reveals a woman torn between her responsibilities and her passion, who ultimately found solace and meaning in the act of writing. She wrote about the transformative experience of integrating her past experiences and studies into a unified whole through writing, and emphasised how this process was integral to her understanding of ikigai.

She was so moved by writing about the ikigai that she had to reassure herself - and her children - again and again. In January 1960, she began writing and recording her notes:

„At night I was again absorbed in writing about ikigai. Because the ideas were bubbling up inside me, I played quiet piano pieces for an hour, partly to put my children to sleep, partly to calm myself down. What a moving experience it is to be able to combine all my past experiences and studies with my writing into a unified whole.“

The emotional resonance of her writing journey is palpable in her reflections. The completion of her first draft in September 1961 was a moment of profound fulfillment for Kamiya, bringing her a sense of peace so deep that she felt she could "die in peace." This statement is a testament to the significance writing held in her life, surpassing even her notable achievements as a doctor and her commendable work with leprosy patients.

Kamiya's diary entries offer a glimpse into her inner world, where writing about Ikigai was not just an academic pursuit but a personal pilgrimage towards understanding the essence of life itself. Her writings were a conduit through which she could distill her life's work, her struggles, and her revelations into a message of hope and purpose, not just for herself but for all who would find guidance in her words. Through her dedication to writing, Kamiya found her Ikigai, demonstrating the profound impact of embracing one's true passions and the transformative power of articulating one's innermost thoughts and discoveries.

Finishing her work on Ikigai

It was far more important to her than her work as a doctor, although she was well known for it. A few days later, Kamiya wrote in her hand notes (jap. "shuki"):

„Finally, it is the last day of the semester break. As I prepared for the upcoming lectures, I looked back on this summer of devoting all my time to my book. The more I wrote over the summer, the clearer it became that this was my most important task. I could almost say that I lived only to write this book. [...] That the meaning of my life would one day gradually reveal itself to me in this way, I really never thought possible.“

What we can learn from Mieko Kamiya about the Ikigai

Ikigai-ni-Tsuite by Mieko Kamiya, First Edition 1966

Mieko Kamiya, through her work as a psychotherapist and researcher, brings us close to the original ikigai in a very personal and at the same time scientific way. We can see a big picture of Ikigai from her biography, her work "ikigai-ni-tsuite", from her personal accounts, self-doubts and through her rich cultural and spiritual experiences in the USA, Europe and Japan.

At the same time, it remains a challenge to translate Ikigai into our Western world and to transpose Ikigai philosophy into our context.

Hereby a reduction of complexity is threatening, which is completed in the error to the Venn diagram of Andrés Zuzunaga.

Mieko Kamiya on The challenge of translating ikigai

„It seems that the word Ikigai exists only in the Japanese language. The fact that this word exists should indicate that the goal to live, its meaning and value have been problematized in the daily life of the Japanese soul. (...).“

Mieko Kamiya highlights the cultural and linguistic complexities of translating "Ikigai." She suggests that "ikigai" is exclusive to the Japanese language, reflecting the significance of finding meaning and value in life within Japanese culture. The word encompasses various meanings, such as strength, happiness, usefulness, and effectiveness.

Kamiya concluded that the closest translations of ikigai in languages such as English, German or French would be "worth living for" or "value or meaning of life." However, these translations may not fully capture the essence of ikigai, which resonates deeply and broadly due to its ambiguity. According to Kamiya, this ambiguity is not a limitation but a strength of the Japanese language, allowing for a richer and broader interpretation of ikigai compared to the more defined concepts in Western cultures.

Kamiya emphasizes the difficulty of cross-cultural translation and understanding, particularly with concepts deeply influenced by a specific culture. This highlights the broad and profound nature of ikigai, which encompasses more than happiness or life satisfaction. It includes a holistic sense of purpose, usefulness, and effectiveness in one's life.

„According to the dictionary, ikigai means “strength needed to live in this world, happiness, being alive, usefulness, effectiveness”. If we try to translate it into English, German, French, etc., there seems to be no other way to define it other than “worth living” or “value or meaning of life”. So, compared to philosophical theoretical concepts, the word ikigai shows us how ambiguous the Japanese language is, but for that very reason it has a resonant impact and a wide scope.“

Mieko Kamiya Ikigai Definition and Viktor Frankl’s Search for Meaning

Mieko Kamiya's exploration of ikigai was linked to the teachings of Viktor Frankl, particularly his concept of logotherapy, which focuses on the search for meaning in life as a central human motivational force. Kamiya's adaptation of ikigai into two distinct forms - ikigai as the source or object of life's value, and ikigai-kan as the emotional state or "sense of meaning" similar to that described by Frankl - underscores the nuanced understanding she brought to the concept.

„There are two ways of using the word ikigai. When someone says “this child is my ikigai,” it refers to the source or target of ikigai, and when one feels ikigai as a state of mind. The latter of these is close to what Frankl calls sense of meaning. Here I will tentatively call it ikigai-kan to distinguish it from ikigai.“

Kamiya found a parallel between Frankl's experience of trauma and her own work with people who have endured profound suffering, such as lepers.This common ground in her research highlights the universal nature of the search for meaning, transcending cultural and individual differences.

Drawing on Frankl's logotherapy, Mieko Kamiya bridged Western psychological theories with Japanese philosophical thought, enriching the discourse on human motivation and the search for meaning. In her dissertation and subsequent works, Kamiya explored this synthesis of ideas, drawing on Western psychology to articulate a model of ikigai that resonated with both her personal experience and professional observations.This approach demonstrates the interdisciplinary nature of her work, which encompasses not only psychology and psychiatry, but also philosophy and existential inquiry.

Kamiya's reference to Frankl's teachings and the integration of his concepts into her understanding of ikigai illustrate the depth of her scholarly engagement with the subject.Her work exemplifies how cross-cultural dialogue and interdisciplinary research can enrich our understanding of complex human experiences such as the search for meaning and purpose in life

Ikigai and Discovering Life’s Meaning

However, she never lost her poetic gift, as we can see in her diaries and throughout her works.

The following quotation is a beautiful testimony to this:

„When we wake up from sleep, we are greeted by the morning. We did not create the morning; it somehow came to give us the chance to live another day. We wake up and discover the morning. The meaning of life is like the morning.“

Dive Deeper Into Ikigai

We hope this article has been helpful. If you would like to delve deeper into the authentic meaning of Mieko Kamiya's Ikigai, take our Free Ikigai-Test and check out our live and on-demand Ikigai course offerings.

Mieko Kamiya’s Life as a table:

| Time (Years) | Life Stations | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1914 - 1931 | Childhood | Born on January 12, 1914, in Tokyo, Japan, to Tamon Maeda and Fusako Maeda. Her father was a prewar Japanese ambassador and postwar Minister of Education. She received an English and Christian education. |

| 1932 - 1937 | Higher Education | Studied at Jean-Jacques Rousseau Institute and the International School of Geneva. Entered Tsuda College in 1932 and later pursued medicine at Tokyo Women's Medical University. Contracted tuberculosis but recovered. |

| 1940 - 1944 | Medicine | Graduated from medical school in 1944 and specialized in psychiatry at Tokyo University. Treated patients and continued her studies after the war. |

| 1945 - 1946 | Post-War Activities | Assisted her father, who was Minister of Education, and worked as an English-speaking secretary. Translated papers and examined a prisoner of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. |

| 1946 onwards | Marriage and Later Career | Married Noburoh Kamiya, an instructor in botanical research. Became a professor at Kobe College and Tsuda College, teaching psychiatry and French literature. Published the book "On the Meaning of Life (Ikigai Ni Tsuite)" based on her experiences with leprosy patients. |

| 1979 | Death | Passed away on October 12, 1979, at the age of 65, due to heart disease. |

| - | Notable Translations |

|

| - | Contributions |

|

* in 2012, Andrés’ Zuzunaga Purpose published a Venn Diagram in the book by Borja Vilaseca called “Que Harias Si No Tuvieras Miedo” –“What would you do if you weren’t afraid?”). It is related to philosophical and psychological Cosmology.